March 25th, 2025: Greetings from Austin! Been meaning to ship this essay for a while. I hope you like it!

+ If you missed it, my anti-hustle culture reflections seemed to make a lot of people smile last week.

+ Congrats to a friend, Jenny Wood, who just launched her book Wild Courage. She’s someone who really seemed to thrive in the corporate environment by being her full-out wild and shameless self. If you like bold perspectives on crushing it on a more traditional path, you might like this one.

Onward…

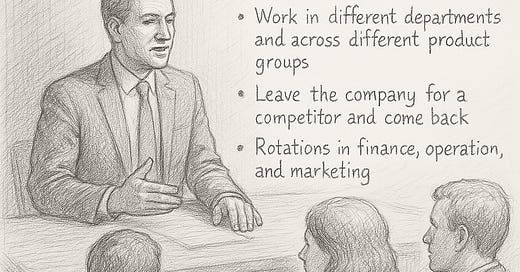

I. The CEO & The Plan

As we sat there, he detailed the entire plan. At 23, as he told us, “I decided I wanted to become CEO of the company.” He sat there and walked us through his playbook, 25 years in the making:

Stints in Asia and Europe

Work in different departments and across different product groups

Leave the company for a competitor and come back

Rotations in finance, operations, and marketing

We were helping the Board assess the next candidate for CEO, and he was by far and away the best candidate. Polished, experienced, and an unmatched resume. No one came close in terms of such a diversity of experience.

I was stunned.

Do people think like this? They set out to be CEO of a company and go for it, step by step?

At that point, I was less than a year away from blowing up my life and starting over. I had been bumbling through the corporate world as a consultant, jumping ship every time I felt dissatisfied. I had nothing close to a plan.

II. “Long-Term Games”

There’s a phrase that has been popularized in online and tech circles by Naval Ravikant: play long-term games with long-term people. It sounds nice. For some time, I claimed this was what I was doing, too.

But upon further reflection, I suspect most people, including myself, are not playing long-term games at all.

Naval’s frame is anchored in 2010s-era Silicon Valley, which happens to be one of the greatest wealth creation scenes in the history of the world.

As he said in an interview:

So, if you’re in a situation, like for example you’re in Silicon Valley, where people are doing business with each other, and they know each other, they trust each other. Then they do right by each other because they know this person will be around for the next game.

If you were in Silicon Valley toward the end of the 2010s, you saw evidence that this “game” worked: everyone who was around for more than ten years was successful and likely rich.

But were most people pursuing the long-term game?

I say no.

III. What is a long-term game, then?

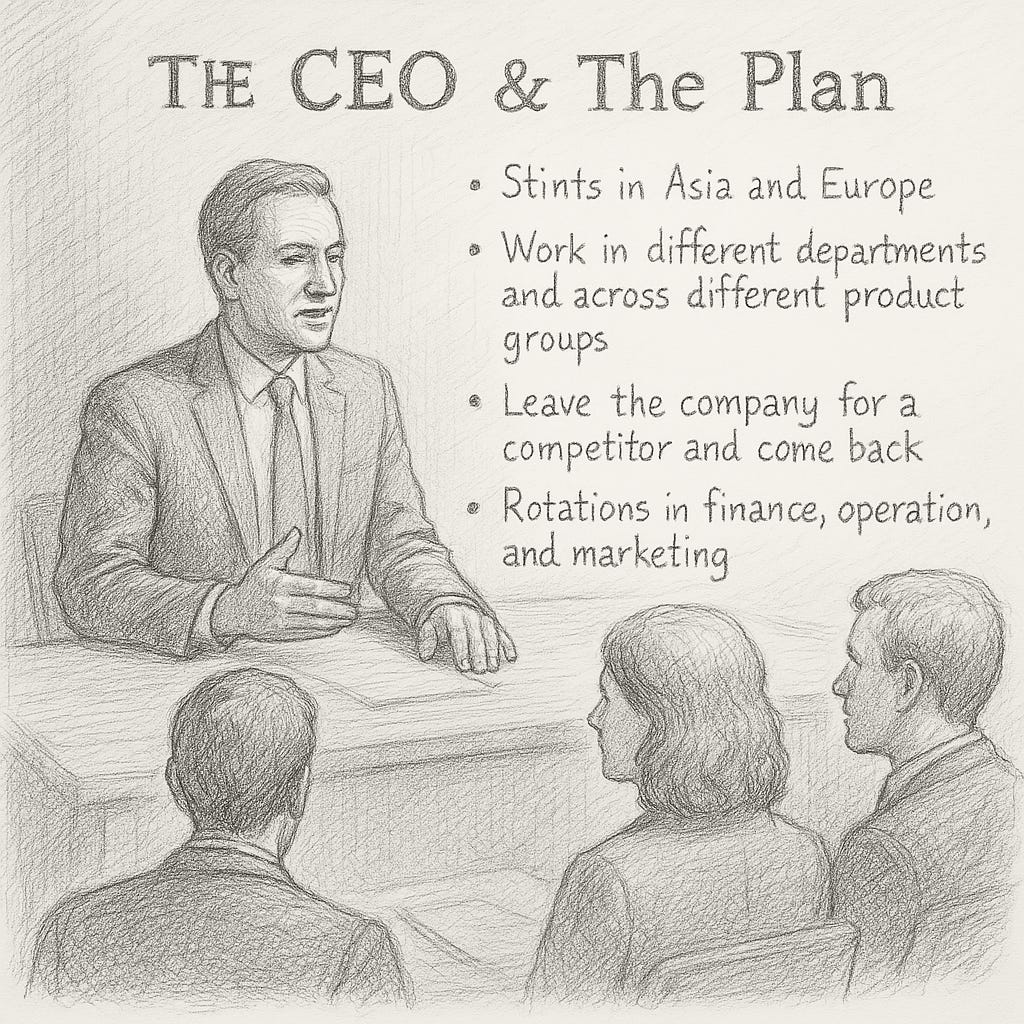

After starting a draft of this essay, I met Luca Dell'Anna in Austin, who was visiting from Italy. He had written ten books and asked if I wanted a copy of his latest. He pulls this out.

What the hell?! How?!

The right book at the right time.

I eventually dove into the book and found it thought-provoking. It also made me sit with this essay for a few more months.

He proposes that long-term games can be described as follows:

First, long-term games are a series of connected short-term games toward a long-term objective, and you play short-term games NOT to win them but to increase the odds of success

One of the most important things in a long-term game is to know and avoid common sources of failure.

To play a long-term game, you need a strategy. The strategy should maximize the odds of success as much as possible.

He differentiates short-game and long-game players as follows:

A short-game player only cares about their growth rate right now

A long-game player only cares about sustainable success (put another way, they “don’t care about unsustainable success”)

The implications of these definitions are pretty interesting because if you have long-term goals and are committed to them, the information you are getting from the people around you about which kinds of strategies to pursue is usually not helpful. This is because the only thing that will be sustainable (for you) over the long term is a game fundamentally aligned with your nature.

We can see then, that if most people are pursuing similar goals in similar ways, most people are not playing long-term games but simply going with the flow of the default game around them.

So we can say that if most people in a scene are pursuing the same strategies, like in Silicon Valley in the 2010s, we should be skeptical that any of them are playing long-term games. They might be around for the next game but most people are more likely to shift when the incentives shift.

Instead, I think the more charitable interpretation of what’s going on in Silicon Valley is not that there are people thinking long-term at all but that an environment exists where being more generous and helping others succeed is rewarded and this is different than many other parts of the economy.

IV. Enter Bryan Johnson

Bryan reminds me of the CEO from the beginning.

In a recent podcast, he told Sam Parr:

It was at 21 where I finally came alive a little bit, and I thought, “You know what? I really want to spend my life doing something that’s going to change the course of humanity.

His goal: be someone that’s remembered in 2500. Crazy, I know.

His first iterative short-term game to get there? Get rich. By 27, he landed on a startup that was working. At 34, mission accomplished. He sold his company, Braintree, for millions. He could have made more, he claims, but sold because, “if I had waited longer, the opportunity to make a lasting impact might have passed.”

So he cashed out and went out to “find his thing.” He gave himself ten years:

I started this at 34, assuming it would take me 10 years to find my thing—something that would be respected by the 21st century.

He saw what other people were doing around him and decided not to do any of those things:

“I held about 12 dinners across the U.S. with some of my closest friends and my smartest people. … After 12 dinners, I like, ‘Okay, now I have my map of what not to do. Now I need a map of what to do.’”

He eventually became a biohacker, spending up to $2 million on his body per year. He landed on a clear goal in the last few years: don’t die. He wants to extend human longevity and potentially “solve” mortality.

I’m not here to go much deeper into Bryan or debate the good/bad of such efforts, but it is impressive how much fun he appears to be having pursuing this from the outside. That seems rare.

But what I think makes this a long-term game is no desire to exit.

V. In the 2010s, most people ended up exiting, one way or another

If you were fully “in it” in the tech scene of the 2010s, it may have felt like a game you would play forever. But a lot of what was happening was short-term games and short-term optimization.

Most people did not want to participate for 30+ years or even 10+ years. They wanted to secure the bag, a literal exit, or to downshift to a more comfortable Big Tech job.

This is fine, of course. It’s a reasonable strategy in an economy where employers aren’t loyal, and the returns to employment can vary so wildly on industry and geographic location.

I saw this gold rush up close. Graduating from a top-tier MBA where the explicit goal is often to pursue the highest-paying “normal” jobs in the economy, I saw a flight to the tech industry in the 2010s. There were two clear strategies:

Move to a big tech firm and get more and more compensation and stock every year

Move from startup to startup, gathering lottery tickets for eventual success

Both “worked” because the 2010s were long, and people got in early. It’s astounding how much wealth some of these people have accumulated from otherwise normal jobs.

However, judging from the streams of broken founders and tech workers in seasons of rest, recovery, quiet quitting, coaching, and angel investing, many likely underestimated the hidden sources of failure on those paths.

For most people, they simply weren’t long-term games.

As Luca points out, “short-term success is going to be more likely due to luck and/or short-term optimization.”

VI. To play a unique long-term game, you must avoid comparison, which is harder than it seems

The problem in an economy is all the other damn people.

If we dare to live and succeed on our own unique long-term game, we must avoid comparison, especially with those currently experiencing short-term success:

“If we act upon the desire to emulate those growing faster than us, we are more likely to imitate short-term optimization than competence.”

To Luca, playing long-term means embracing the “fastest reproducible growth rate over time.” But the limiter on this is the actual game that you can sustain personally.

More simply: “Playing long-term games has nothing to do with delaying gratification - only with delaying comparison.”

Delaying comparison is hard. It is much easier to fit in and succeed like everyone else than to pursue your long-term game.

Even if we are to succeed in copying other people’s strategies and making them our own, we are often oversimplifying the factors that lead to someone else’s success.

For example, we might see someone succeeding in the short term who is hard-working and motivated and assume that their strategy can be replicated by being motivated and hard-working.

We may be missing the fact that personal wealth or a trust fund is funding something that appears to be a success but may well be a money-losing endeavor.

Ultimately, a long-term game must be unique to the individual. This is because to maximize the odds of success and design against failure, you must design a strategy around your unique advantages and disadvantages.

VII. While I’ve often felt like a fool, I don’t think I’m playing any sort of long-term game. At best, it’s a medium-term game, which may be more attainable and interesting than long-term games anyway

As I’ve said from the beginning of my journey, my goal is to be on a path that I’d be excited to stay on. I want to maintain this until I'm 60 years old, if not longer.

But I’m not aiming at anything. There is no long-term objective as Luca defines it.

But I usually reject most short-term optimization at the same time.

I would describe my “game” as follows

Continue to buy the time to do creative work, like this, for fun, and for “free”

Connect with others around these ideas, engage in a broader “conversation” of ideas with people, other books, articles, and so on

Put out things that can be sold and fund my journey but don’t require enormous or fixed time commitments

Repeat

For almost eight years, this approach has “worked.” I’ve kept things small and simple, ignored the strategies of many people around me, like scaling teams, launching fancy cohort-based courses, and doing traditionally published book deals, and instead prioritized doing my good work while preserving time freedom.

Maybe we call this a medium-term mediocre game (MTMG): playing a game simply to keep playing, hopefully for a few more years each time.

There is no long-term objective, arrival, or accomplishment, and that’s okay.

Instead, the underlying characteristic of this approach is stubbornness:

I'm stubbornly committed to my current path because I’ve deemed the most popular and common paths off-limits.

This is an interesting constraint because it forces me to constantly think about the strategies I’m using and also helps me resist comparison because I know that most other strategies definitely won’t work.

It’s also a good approach for me because for almost eight years, it’s been quite fun, has led to some pretty interesting places, and most of all, it continues to work.

VIII. What if everyone wants to exit?

In Ravikant’s essay, he added toward the end: “Sometimes people betray each other because they’re just like, ‘I’m going to get rich enough off this that I don’t care.”

He’d probably argue that Silicon Valley had more of this spirit than he might have thought ten years ago.

For the most part, I don’t blame anyone. But what’s concerning is that this spirit of exit is becoming the de-facto goal of many people.

People want to hit it big with equity compensation at the right company

Work for the highest paying companies no matter what they have to do

Founding companies just for the chance of an exit, even if they don’t care about the underlying business

These aren’t long-term games. These are stay-in-until-I-can quit games.

And existing ultimately can be a risky life choice. Here is Loom’s founder Vinay Hiremath, sharing his reflections after exiting his own company:

Life has been a haze this last year. After selling my company, I find myself in the totally un-relatable position of never having to work again. Everything feels like a side quest, but not in an inspiring way. I don’t have the same base desires driving me to make money or gain status. I have infinite freedom, yet I don’t know what to do with it, and, honestly, I’m not the most optimistic about life.

In the past, this sort of early retirement or escape was restricted to places like Wall Street, but even then, most people didn’t really have a goal of retiring early.

This idea of playing to exit is widespread. Young people see the whole economy as rigged. “Secure the bag” has emerged with Gen Z, a hat tip to the idea that you should take care of yourself first.

I think this is a bigger shift than people think. It’s basically nuking collective trust in the system, the story that the broader economy is somewhat fair and meritocratic, and if you commit to work over a long period of time (the economy’s long-term game), then all will be okay.

This is why I think finding your Good Work is important.

It makes you want to stubbornly commit to something.

It reframes work from something to escape to something to enjoy.

It nudges you to go after things you care about, especially over medium time horizons.

Ultimately, it nudges you to participate, engage, and be useful.

IX: Long-Term Games Are Rare

Was that eventual CEO really playing a long-term game or just telling us something impressive in the interview?

We’ll never know. But it is worth noticing how rare that kind of thinking is and how impractical it is in today’s economy.

I think the most interesting thing about the widespread use of the phrase “long-term games” is simply that most people aren’t doing anything close to it.

For most people, things like “medium-term games,” ones you want to commit to for 5-10 years, are probably a worthwhile level up to their current ambitions.

And for the ones who want to go longer? Stubborn games are the way to go. Find weird principles you won’t compromise on and then live it full out.

+ Luca’s book is very dense with interesting insights on long-term games. You can grab it here.

Keep reading

No, Everything Doesn't Have To Suck | #291

March 17th, 2025: Greetings from Austin! I had a ton of fun with today’s post. I think you’ll like it. Please share this if it makes you smile or laugh.

Two years a dad | #289

There is no single moment where I felt like I had finally inhabited the role of “dad.” There are so many clichés and stories in the way people talk about parenthood that would be easy to repeat but nothing has felt right.

40 Thoughts On Turning 40 | #287

February 10th, 2025: Greetings from Oaxaca. What a beautiful place. We took some fun pictures. and oh, and I turned 40.

We shall stubbornly continue on this medium-term game…

Which I’ve been doing since 2015. I’ve somehow figured out how to hack a living doing things like this.

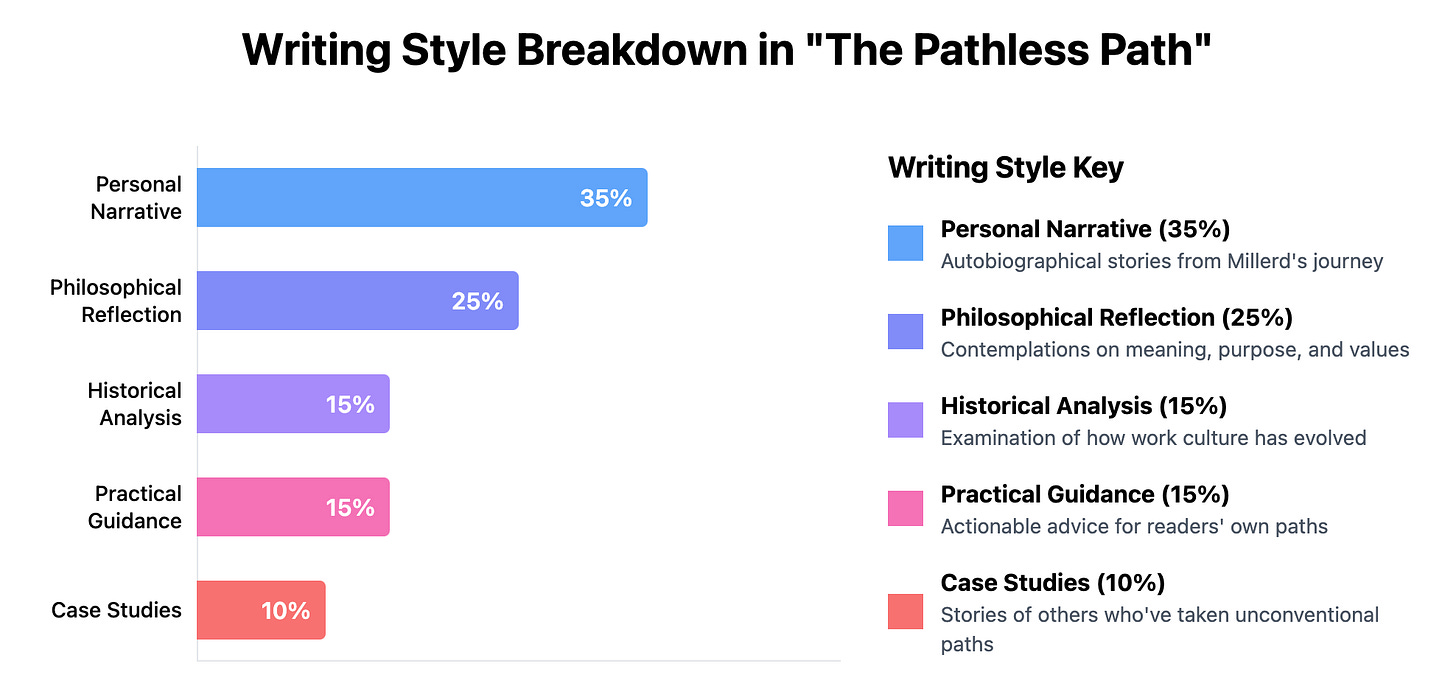

If you like what you read here, you’ll probably enjoy my books The Pathless Path and Good Work. I recently asked Claude to break down the writing for The Pathless Path. I suspect this might be an interesting way to show you how the book might be different than you expect:

If you’d like to meet others on “pathless paths”, you can join The Pathless Path Community.

Some things I endorse: Crowdhealth, an alternative to US health insurance, Kindred, a home sharing app, and Nat Eliason’s Build Your own AI Apps course.

If you received this and find yourself in a state of outrage thinking, “How the hell is this drivel allowed in my inbox?” I strongly encourage you to unsubscribe below. It is your god given right and there is plenty of good stuff online.

A reminder: I don’t check unsubscribe alerts and never look at my subscriber list. So if you feel like unsubscribing, you can do so below.

I worked with Bryan through the transition you describe and it’s not quite right. His script was more Step 1: get rich. Step 2: do the most impactful thing possible with the money Step 1 was really sublimated Mormonism as he’s openly talked about. Step 2 initially landed on launching kernel. All the longtermism came out of thinking he did circa 2017-18, including with me. Iirc the “remembered in 2500” possibly came up in one of our chats as a test of impactfulness more than longtermism for its own sake. The way you might measure the size of a nuclear explosion by how far away the shock wave can be felt. It’s been a while but I think our biggest frame for all this was James Carse infinite game. I haven’t really worked with him since he got on the blueprint thing, since that’s way out of my interest and wheelhouse, but from occasional casual check-ins I gather he’s still thinking about the philosophy in similar ways. Our views on AI and death have… diverged let’s say 😂

I like the quote, "Comparison is the thief of joy."

That sucker has a bit to answer for!