September 30th, 2023: Greetings from Taichung, Taiwan. We’re celebrating mid-autumn moon festival with family for the weekend! Here’s a video

from the train down south last weekend:

+ My friend Ravi is hosting a quarterly goal planning session today and Tuesday. He’s one of the most thoughtful people I know and is an interesting mix of tech founder and practicing Zen Buddhist. Check out more here (non-affiliate).

+ I’m going to experiment with an influencer campaign for my book in November. If you have a sizeable audience and would be interested, let me know!

The Individualism Myth

As someone who has a creative spirit and likes to question authority, I feel lucky that I grew up in the US. Our obsession with doing your best and succeeding as an individual made it easier to change jobs often and less risky socially to quit a good job and do my own thing. It made it easier to find others doing things like that too. It’s no surprise that the internet feels dominated by Americans, the last frontier in a country that always needs to be pushing into new territory and trying new things.

But we are a country of extremes. It’s a place where you can chase after bold goals and be rewarded but also receive no pity if you aren’t wired for the kind of achievement that seems to work in the modern economy. The unspoken reality of the individualism script in the US is that it’s not actually for everyone anymore. While previous generations could find good jobs for life with a high school diploma, this is no longer true. Everyone knows that you need a bachelor’s if not a master’s to keep up.

The success script that I grew up with was great for someone who had a path to success but unusually cruel to someone who wasn’t as lucky. The message I received about success from our culture wasn’t really about aiming at excellence or finding something I loved doing but rather that I should be motivated as hell because the punishment for not trying to achieve things was that I might end up poor, a fate worse than most other things.

It follows then that as Americans, we become obsessed with money. How to earn it, knowing what different professions earn well and those that don’t, and the fundamental lesson: that life is a money problem, where the path to living a “good” life is merely a result of making enough money. Money metaphors dominate reality as people say time is money, money talks, and then drop their two cents. We obsess over billionaires on our attention capture screens and discourage our kids from becoming teachers or social workers because we don’t want them to end up poor.

The crazy thing is that these stories and ideas are deeply connected if not highly dependent on the economic circumstances in which they emerge. But almost no one acts as if that is true. Oshan Jarow points this out in an essay on “acid capitalism”:

We're subliminally dosed into believing that our holistic experience of what being alive is like - our consciousness - is a given, rigid, natural phenomenon that cannot be meaningfully altered by such man-made, social constructions as economic policy. All the while, exactly that is happening.

An example of one of these deeply held beliefs comes from a fascinating conversation between poverty researcher Jamila Michener and Ezra Klein. In it, Jamila talks about a successful homelessness program in Illinois. They were giving people free housing, and it improved the situation by a lot, reducing the homeless problem by 70%. But the state pulled back on the program because, well, you just can’t give people something for nothing:

But it just couldn’t live politically, even though it was working, even though it was helping people— couldn’t live. And when I asked my students why, they’re never surprised. They’re like, oh, of course, because you’re giving people something for nothing. Even if everyone is better off, we still don’t want to give people something for nothing, especially not certain people, not those people.

This may be surprising for people from other countries, but it is not surprising at all having grown up in the US. We take our individualistic streak seriously and the belief that one needs to “earn” their success is deeply embedded in American mythology.1

Jamila, likely having grown up in the US wasn’t shocked about it. She took it for granted that this was what people thought. It was just that she didn’t really think anything would change until people unlearned this story:

And that is a hard constraint in our politics when it comes to the politics of poverty. And we will have to unlearn, figure out how to unlearn some of that thinking on a societal level to really make transformative change that gets us to a point where poverty isn’t a thing in one of the richest countries in the history of the world.

I think she is right but not because I want to level the playing field for everyone but because I just don’t think that today’s labor economy can’t deliver on our beliefs about how the world should work. A labor economy is really just a collection of incentives and doesn’t give a damn about what people believe about how things should work. David Autor has been trying to point this out for nearly a decade, with research showing how middle-skill jobs of the past are no longer guaranteed:

In the industrial era, many Americans, even if they didn't necessarily excel at school, could find good jobs doing what Autor calls "middle-skill work." These were jobs that required workers to know how to read, do basic math, and possess other skills, but they didn't need the type of elite skills typically acquired through years of education. Workers doing middle-skill jobs usually followed formal instructions, like "insert this widget here and turn twice" or "take all our receipts, create a document tracking them with this typewriter, and then add them all up."

Middle-skill jobs were commonly found in places like factory floors, or in offices, doing bookkeeping, compiling paper records, calling suppliers and clients on the telephone. And it turned out that they paid relatively well. It's why, Autor says, "The industrial era helped really grow the middle class."

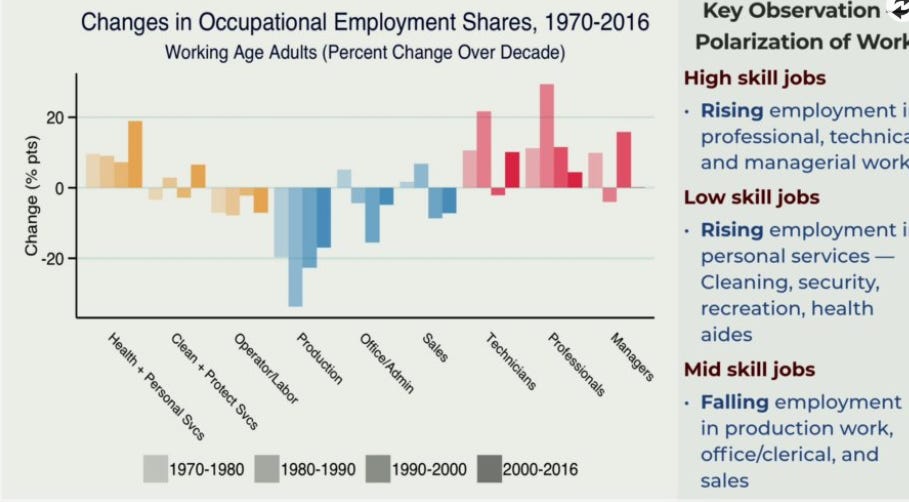

His research has showed that these kinds of jobs have been declining steadily for decades. What killed them? Technology. And this is the challenge of the modern age. Technology can deliver productivity gains and increased prosperity but often at the loss of middle-skill middle-class jobs. This led to “job polarization” as Autor calls it, increasing the number of high-wage jobs and low-wage jobs while hollowing out the middle which you can see in the blue bars below:

Of course, more high-wage jobs are a great thing but the thing that people don’t want to talk about or even know how to is that the default path is no longer a middle-class game. It has been supercharged into an upper-class game, one that no longer depends on getting a job and working hard but requires getting the right credentials, building the right network, and staying adaptable and learning the latest skills and language required to compete for the best jobs, not to mention moving to the right cities to build those networks. But the fact that the “game” has gotten harder just ends up reinforcing the individualistic narrative of the “self-made” person, because, well it does take a lot of effort to succeed.

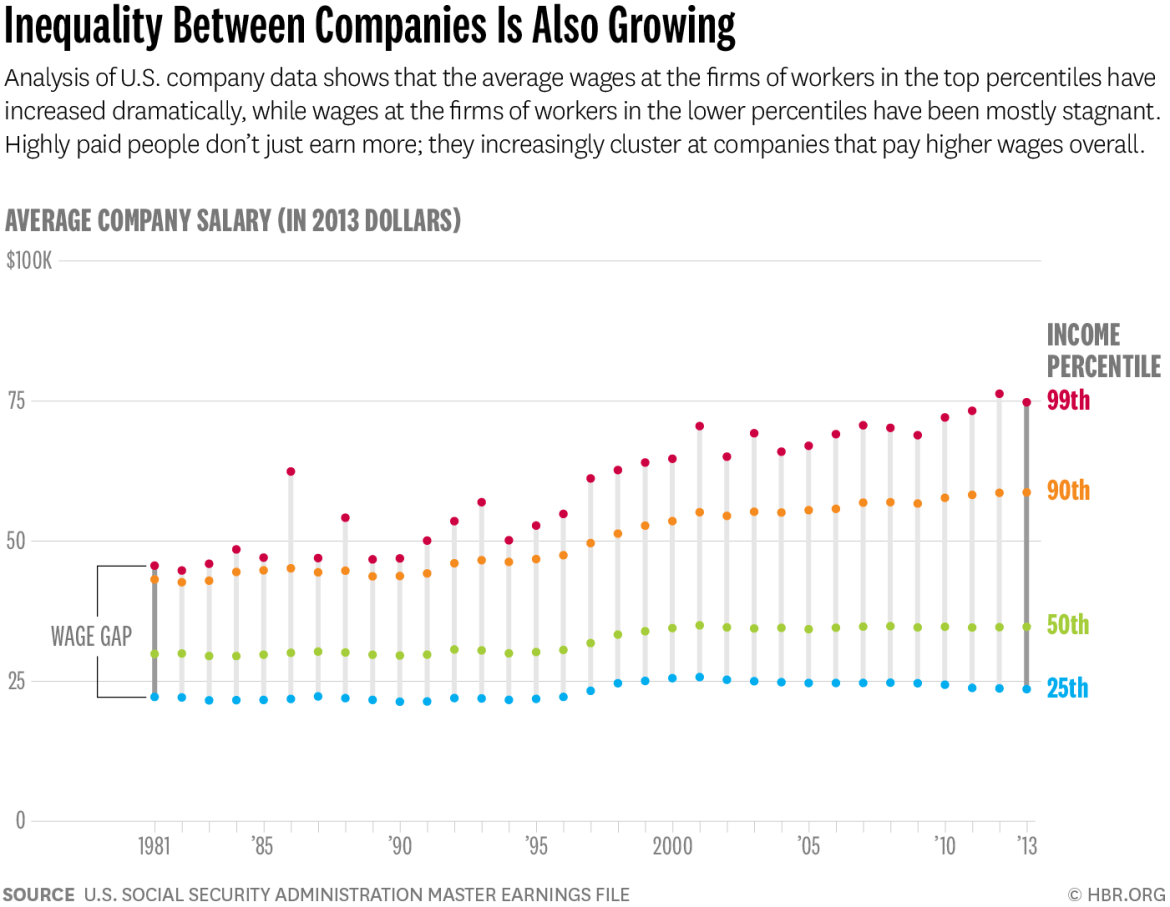

But "hard work” is increasingly disconnected from economic outcomes. The best predictor of how much money you make is not going to be how hard you work but how profitable your industry and company are. Fifty years ago, there might not be much difference between most jobs at places like GM, GE, Boeing, Westinghouse, AT&T, or US Steel. A marketing person might make a similar amount to a finance person and an executive might not make radically more than a middle manager. But now the disparity between a job at a company like GE and Google is profound. And then within a company like Google, the difference between a marketing person and a software engineer is going to be even more extreme. There’s a reason most of my business school classmates transitioned to working in tech, and specifically the magnificent seven, since graduating ten years ago. They didn’t suddenly all become interested in technology, they just knew where the money was.

The individualism story in the US is a great one. Work hard and you can make it. But this kind of story works best with a robust labor market that can deliver “making it” as a service for vast amounts of people. Becoming self-employed, I am far more aware of how much making it is dependent on support from others and a system that enables self-employment, gig workers, and free movement. In a weird way, full-time jobs gave me more of the illusion that I was doing it all on my own because so many of the things that contribute to people’s success like labor laws, employer-based healthcare systems, social approval, national trade advantages, and dollar supremacy were baked into the system as defaults. But now more than ever to really succeed as an individual you need more support from others than ever: parents that can pay for good schools and a network of friends and family that can help you along the way.

Will we update our scripts and stories about how the world actually works? Or is this a conversation that people just don’t want to have? Is it easier to pretend that everyone can make it?

I don’t have good answers to these questions, but I sense the disconnect between what people believe at a societal level and the market finding reality of an economic system have created lots of anxiety and discontent. Most people don’t like to think about life at the abstract level but more than ever, having an accurate map of how the world works is vital.

The US and many parts of the world have benefitted from broad economic prosperity since World War II. But unfortunately, there are no rules in human nature that turn economic abundance into a sense of personal abundance. Our stories are in many ways our reality. We start with our scripts about how the world works and then take action on the world in order to make that our reality. In the US, our oldest generations still believe in the individualistic ethos that they saw as a reality when younger: work hard in an average job and everything will be okay. But the youngest generations don’t see the same reality. They increasingly see choices around work and how to spend their life as a trade-off: risk alienating friends and family by taking an alternative path and challenging their reality and betting on yourself or going along with a system that you and your friends think is rigged. Young people see work as more like gambling than previous generations and we don’t really know what that means for how people will think about work.

+Speaking of interesting reflections from younger people wrote a reflection on leaving her job and how shes rethinking work this week.

To discuss!

What are the updated stories about work you have embraced in the past few years? How are these different than in the past?

Do you have conflicts with people in your family of different generations on how you see how the world of work works?

If you are not from the US, what parts are different in your country?

Thanks For Reading!

I am focused on building a life around exploring ideas, connecting and helping people, and writing. I’ve also recently launched a community called Find The Others. There are weekly writing sessions, monthly “find the others” (literally) virtual meetups, and general supportive vibes.

You can join Find The Others if you want to hang with us too, or if you are already a subscriber, get access here.

If you’d like to support my journey, the best ways are to:

Buy or listen to my book, The Pathless Path (or message me if you want to bulk order at a lower price)

Want to reach 15k+ curious humans? I’m looking for sponsors for 2023 for this newsletter or podcast. Please reach out or book a package here directly.

Subscribe to my podcast and leave a review.

🤳Want To Get Started on Youtube? Friend of the newsletter Ali Abdaal (and his amazing team) have just launched their self-paced course and accelerator program on creating a thriving YouTube channel.

In addition, I recommend all of the following services (affiliate links): Collective for setting up an S-Corp in the US (recommended >$60k revenue), Riverside.fm for HD podcasting, Descript for text-based video editing, Transistor for podcast hosting, Podia or Teachable for courses, Skystra for WordPress Hosting, and Circle for running a community.

A reminder: I don’t check unsubscribe alerts and never look at my subscriber list. So if you feel like unsubscribing, you can do so below.

Of course, we do give many people things for “nothing.” We have a robust welfare system, something I saw first-hand when I had a low income after quitting my job, and we don’t even stop at giving handouts to the neediest. We have lots of welfare for rich people, we just have different names for it like a tax credits, mortgage interest deductions, carried interest, 1031 exchanges, and other impressive schemes.

“Can’t give people something for nothing” encapsulates so well the myth of the self-made individual.

I live in Europe and we have been influenced by the same myth. There is also a social angle. In Northern countries, it’s about finding your spot and doing something that generates tax revenue so that the welfare state can continue operating.

I think we have more acceptance for commonly owned goods and that you don’t need to “earn” access to them. But if someone isn’t employed normally, they may be perceived as freeloaders.

I'm really appreciating your insight -- part-way through your article -- yet this notion of "unlearning" is so unhelpful.

From everything I've learned about learning (NLP plus cross-cultural studies in many forms), the brain can't unlearn; the brain can only learn. So re-wiring or re-learning would be more helpful concept, I believe.

For my fellow Americans, what if we understood that we can change the money paradigms that underpin many people's thinking?

What if we re-wrote the near-invisible thought structures that so many think are just "true" and "just the way it is"?

We can do such things...