#1 Work In A Serendipity Economy

I’ve been reading One Summer by Bill Bryson (h/t

) which is a book focused on a single year, 1927. It focuses on radical movements, Babe Ruth, Calvin Coolidge, and Charles Lindbergh’s first flight and the beginning of the aviation industry. It’s a fascinating book and I love reading stuff like this because it’s where I often stumble on surprising ideas.In the book was the story of Edward Robert Armstrong who was trying to solve the problem of planes not being able to easily cross the Atlantic. While Lindbergh was able to cross the Atlantic in one flight, it was a borderline miracle and also took 24+ hours (planes used to be much slower!).

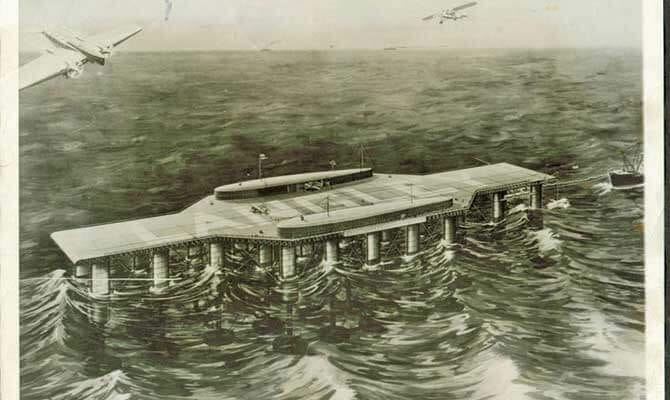

The solution was a bunch of these things, “seadromes,” scattered across the ocean:

He had some strong support at the end of the 1920s but this evaporated when the great depression started:

Unfortunately, that was the week of the stock market crash and his financing fell apart. Armstrong continued for years to try to get his plan launched, reducing the number of proposed platforms to five and then three as planes became more powerful. Eventually, of course, they were not needed at all and his dream was never realized, but his seadromes did form the basis of modern offshore oil platforms. Armstrong died in 1955.

When you look at a modern oil rig you can clearly see the connection:

Right solution, wrong problem, wrong timing!

This is something I think about a lot on my path. How do I figure out what to work on if I cannot figure out what the options are for my work several years from now?

I riffed on this with my conversation with Kris Abdelmessih where he initial got me thinking about this. He gave an example: Duane Reade in NYC. The company thinks like a real estate company instead of a retail store. This is only because the value of the property increased so much that it was worth more to the company than the value it was able to extract from its role as a retailer.

I sense more of modern work is becoming like this. You aren’t working on a manufacturing line where you can see the output of your effort. Instead you are working on something that doesn't quite feel that important but may have unexpected value in the future. Except you can’t quite predict when and how that will take place!

A lot of work that went up in flames during the dot com bust led directly to tech successes in the 2010s and very few people predicted it.

This can be maddening and freeing. Within a company, it might drive you crazy to work on something like the metaverse only to see the company lay off half your team a couple years into it. But maybe eye tracking helps surgeons in 2028? Who knows.

Good for the economy but bad for the soul of someone trying to build a coherent career and work narrative.

My take is that this means we should be default skeptical of any path with a clear payoff. If the payoff or rewards are clear it suggests that most of the personal serendipity and potential satisfaction of the role have been eliminated.

In this kind of “serendipity economy" we will need to loosen our grip on the scripts we grew up with that tell us what to do. But we also must learn to trust ourselves. To have intuition about the things we can only do and then to commit to them no matter the lack of evidence about the payoffs in the short term.

For example, there was no obvious resonance with my writing on work for years. People laughed at me and made fun of me. Some people still make fun of me. That’s fine. But at my core I know there are things I can commit to and keep doing like writing.

Where will the writing take me?

I have no idea but I’m excited to find out.

This issue is sponsored by:

You ditched the traditional path… why haven’t you ditched your traditional health insurance?

Experience the freedom and affordability of cash payments and community-funded healthcare with CrowdHealth. Use promo code “Boundless” during sign-up for a special discounted subscription offer.

#2 Writing & Life Force

I started watching the Jonah Hill documentary focused on his therapist, “Stutz.” The therapist broke from the traditional therapy world early in his career. He talked about an important moment when he said he wanted to help his patients who were depressed feel better as soon as possible. His colleagues scoffed at him and thought that was ridiculous.

He decided to go his own way. Watching it, it seems like Stutz fills the archetype of a coach who happens to have a medical license. I sense these are the real gems in our society. The people who are desperate to figure out what works rather than go along with what the incentive system demands.

He focused everything around activating one’s “life force.” If you’ve read Viktor Frankl’s writings you can see the connection in schools of thought.

He argues that you can’t solve depression directly, you need to focus on the body, relationships, and self.

The core insight: you need to find a mission. You need to find things that matter to you. Without these things, you are doomed.

I think Stutz’s insight about the body is important and I sense that breathwork (see my conversation with Jonny Miller) will become more popular because of this.

From there, Stutz talks about writing as a way to refactor your life. I think this is totally true. I wish more people would write.

Last week Paul Graham shared an essay and this quote touches on why I think writing is so important:

A good writer doesn't just think, and then write down what he thought, as a sort of transcript. A good writer will almost always discover new things in the process of writing. And there is, as far as I know, no substitute for this kind of discovery. Talking about your ideas with other people is a good way to develop them. But even after doing this, you'll find you still discover new things when you sit down to write. There is a kind of thinking that can only be done by writing.

Writing is finding out things you didn’t expect, especially things about yourself.

So many people are gripping so damn hard on an idea of who they think they are.

One session with a pen and paper and you are usually forced to release that grip.

If it worked for me it could possibly work for you.

#3 Sabbaticals

Michelle Varghoose had some great reflections on sabbaticals:

A sabbatical was a blessing because I had the opportunity to step away from the rat race and learn to build a life that was centered around what brought me meaning.

Two years in, I’m now naturally busier as my creative projects have compounded. The word sabbatical is starting to feel like an old sweater that doesn’t fit quite the same way anymore.

I don’t define myself by whether or not I’m working. Instead, I’ve found a new way to engage with life and work that works better for the person I am now. Having that freedom to move away from the corporate world allowed me to develop this new life

#4 Calvin Coolidge Quits

Another quote from One Summer.

I cracked up learning a bit more about Calvin Coolidge:

By 1927, Coolidge worked no more than about four and a half hours a day—“a far lighter schedule than most other presidents, indeed most other people, have followed,” as the political scientist Robert E. Gilbert once observed—and napped much of the rest of the time. “No other President in my time,” recalled the White House usher, “ever slept so much.” When not napping, he often sat with his feet in an open desk drawer (a lifelong habit) and counted cars passing on Pennsylvania Avenue.

Reading a bit more it seems like he never really wanted to be President or at least got tired of it. Here is what Coolidge said in his memoir, deciding against running in 1928:

"The Presidential office takes a heavy toll of those who occupy it and those who are dear to them. While we should not refuse to spend and be spent in the service of our country, it is hazardous to attempt what we feel is beyond our strength to accomplish.”

#5 Intrinsic Motivation

I liked this reflection from

on the craft of coding:It took me a while to realize this, but most people in software don’t care inherently about software. They don’t see it as a medium of creative expression. Instead, it’s a means to some other end, like building a valuable business or earning a lucrative salary. There’s nothing wrong with that, but if that’s your vibe, my approach probably won’t work for you. It’s an extremely hands-on, DIY way of product building. This method has advantages and disadvantages, but it’s only worth it if you find it intrinsically satisfying to build things yourself.

The secret to all work worth doing?

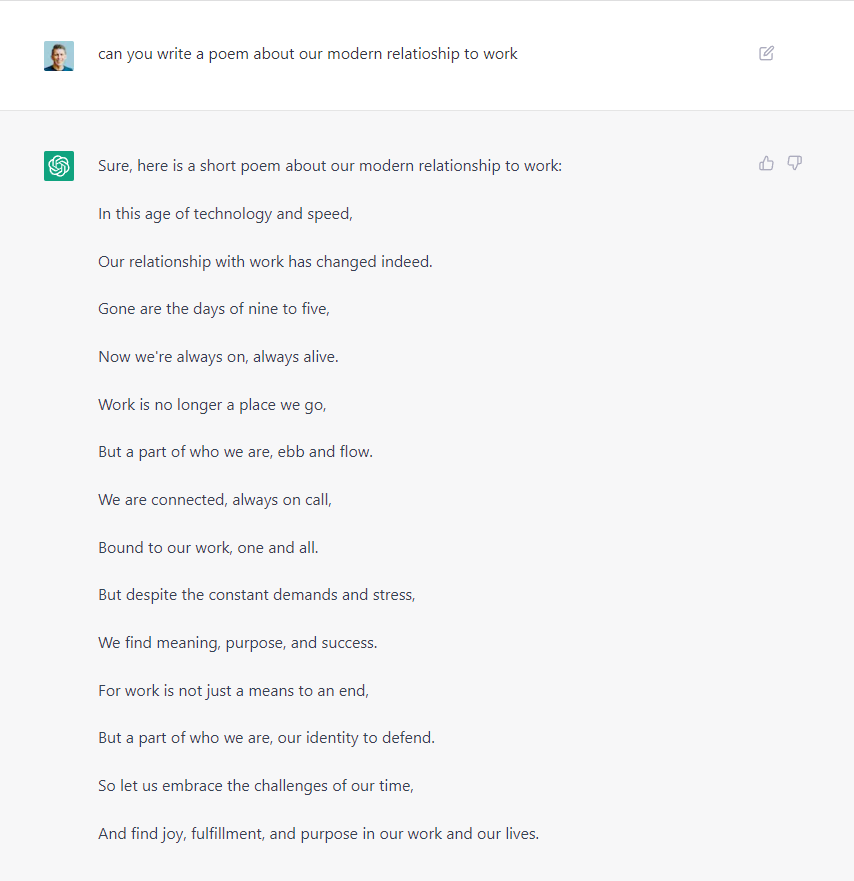

#6 A Poem About Work

In this age of technology and speed,

Our relationship with work has changed indeed.

Gone are the days of nine to five,

Now we're always on, always alive.

Work is no longer a place we go,

But a part of who we are, ebb and flow.

We are connected, always on call,

Bound to our work, one and all.

But despite the constant demands and stress,

We find meaning, purpose, and success.

For work is not just a means to an end,

But a part of who we are, our identity to defend.

So let us embrace the challenges of our time,

And find joy, fulfillment, and purpose in our work and our lives.

This was written by a large language learning model from OpenAI based on this prompt.

Which is pretty wild.

I’ve played around with multiple AI tools over the past few months and am blown away and intrigued by the potential implications. I don’t think we know yet.

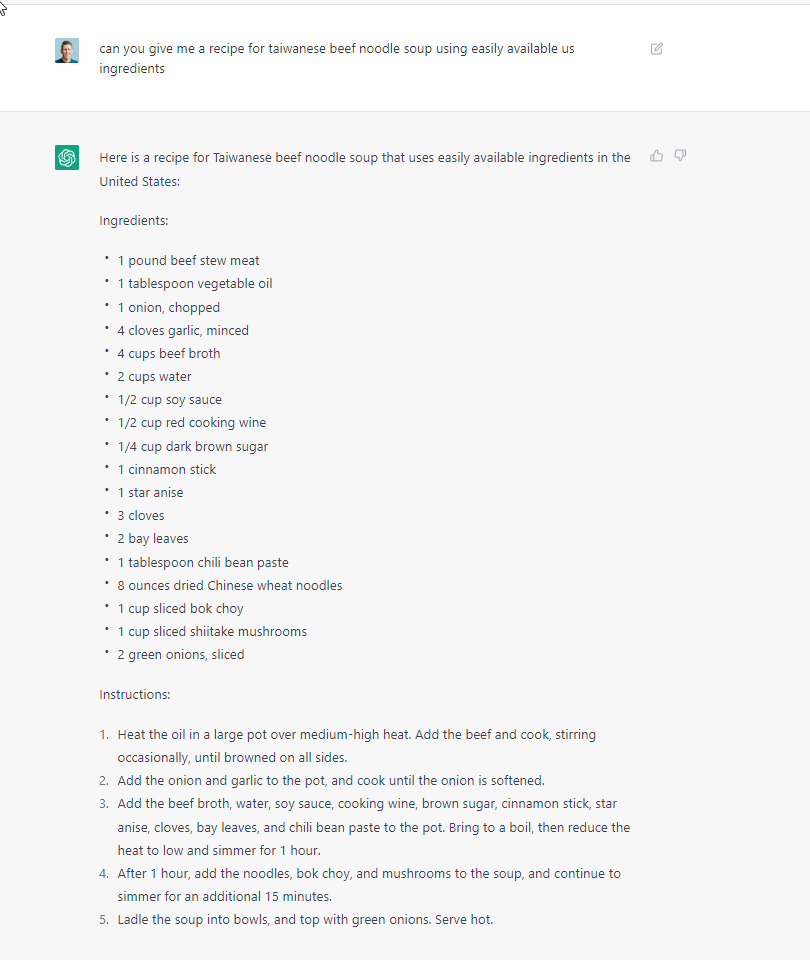

Just look at this amazing response to a question I’ve genuinely struggled to solve on the internet before:

I could say some bold things about what this all means but I don’t have a good feel yet. I am going to keep thinking about it and in the meantime you should try it here and let me know what you think.

For a deeper take on what it means check out

's essay from yesterday:#7 Former McKinsey Partner To Freelancer

Adam Braff grew up in a house where writing was always encouraged. His mother published a newsletter, and his father was a data analytics consultant. He started out as a lawyer, but after the dot-com boom led to a surge in demand for consultants, he decided to make the switch. He now runs his own consulting firm and writes regularly on a variety of topics. Braff himself became interested in consulting during the first dot-com boom.

We talk about what it was like in consulting in the early 2000s, how he ended up deciding to become a freelancers, how writing has played a major role in his journey, and his annual forecasting contest he runs.

Thanks For Reading!

I am focused on building a life around exploring ideas, connecting and helping people, and writing. If you’d like to support my journey, the best ways are to:

Buy or listen to my book, The Pathless Path

Want to Sponsor Boundless or My Podcast? 👉 Find Packages Here

Purchase one of my courses on freelancing or reinventing your path

Subscribe to my podcast and leave a review

Support this newsletter through an ongoing micro-donation with 68 others

In addition, I recommend all of the following services (affiliate links): Riverside.fm for HD podcasting, Transistor for podcast hosting, Podia or Teachable for courses, Skystra for WordPress Hosting, and Circle for running a community

A reminder: I don’t check unsubscribe alerts and never look at my subscriber list. So if you feel like unsubscribing, you can do so below.

Thank you for sharing my essay and for encouraging me on my creative journey!

Also, I always thought "Silent Cal" seemed like an interesting character and your snippet about him is so funny - adding One Summer to my reading list!

Great read, thank you for sharing. Really resonated with the term "serendipity economy." Totally true, we need to learn to live with that uncertainty. Reminded me of one of my favourite books--The Wisdom of Insecurity, by Alan Watts.