Boundless #47: A Super Nerdy Issue - Total Work & Middle-Wage

Deep dive on total work, middle-wage jobs disappear & obsession with employment

April 13th, 2019: Greeting from Taipei!

✌Thanks for the random votes of confidence from Michael & Heath. If you’d like to come on this journey with me, consider becoming a patron of this newsletter by clicking “subscribe now,” joining the Chipotle tier on Patreon. If you’d rather send a tweet, I wrote up this fancy tweet for you (works now)

💵 I updated my financials for March and posted a longer essay about how I cut my cost of living by 75%.

“I personally think that being able to work 996 is a huge blessing…If you don’t work 996 when you are young, when can you ever work 996?”

Jack Ma (on China’s 9am-9pm, 6 day a week work schedule)

#1 Andrew Taggart’s Deep Dive Into Total Work

I wanted to share Andrew Taggart’s most complete talk to date on the concept of “Total Work.” In many ways, his article in Aeon a year and a half ago first proposing this idea sent me down a bit of a rabbit hole and has awakened my curiosity of how we got here in the first place.

In the beginning of the talk he proposes that a number of elements make up our modern conception of work and that the only explanation for these factors is a deeper idea that keeps them going.

Tasks, Projects, Meetings, Careers, Work-Life Balance

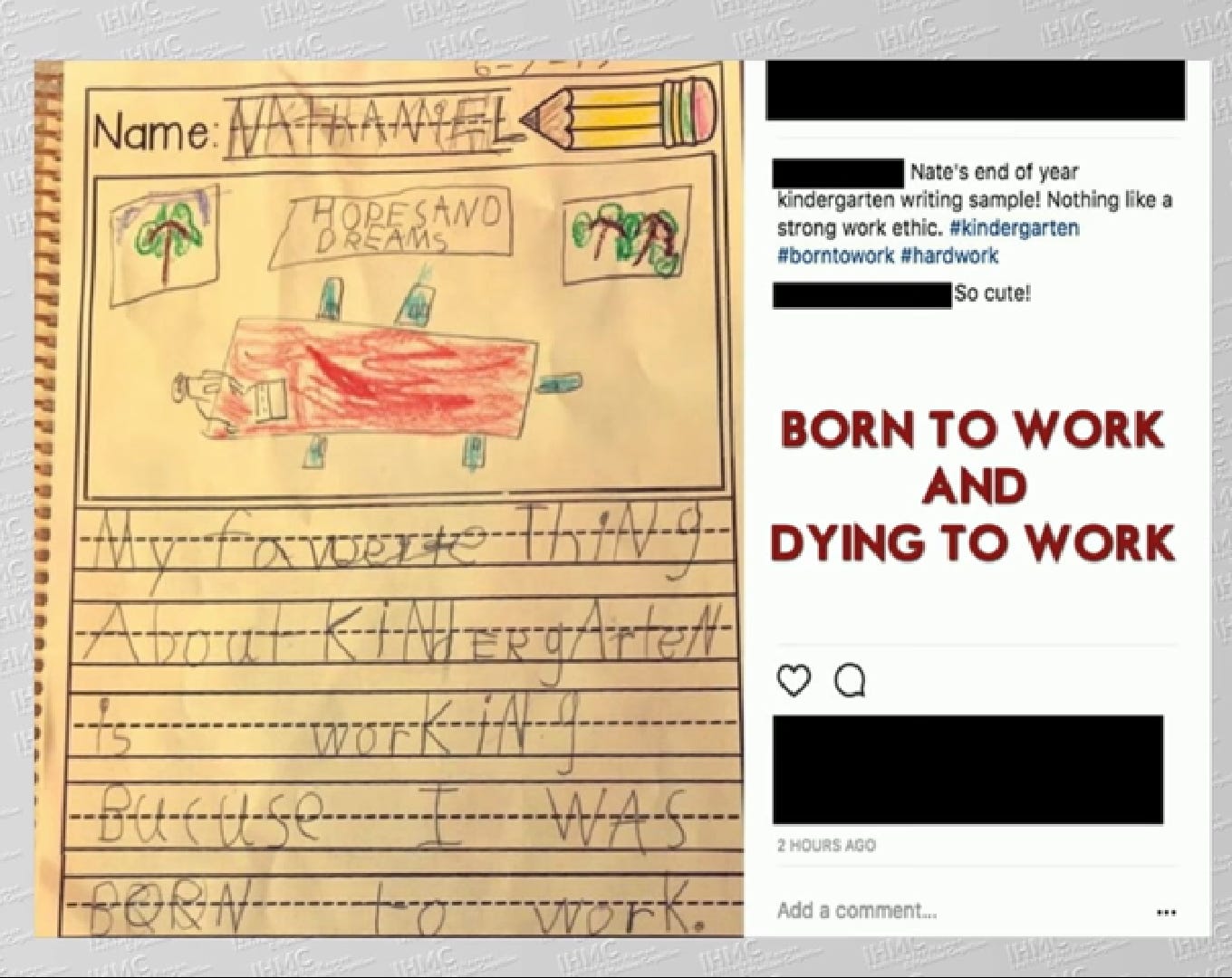

He proposes that “Total Work” is the hidden driver that keeps all of this alive. He summarizes Total Work as the assumption that we “are born to work, live to work and are dying to work”

He offered two powerful examples. The first was a real drawing from a Kindergartner who was convinced that his life purpose was to be on that laptop in the corner office:

“My favorite thing about kindergarten is working because I was born to work”

He also cites Marissa Mayer’s expert advice (because she did it) on working 130 hours:

The actual experience was more like, “Could you work 130 hours in a week?” The answer is yes, if you’re strategic about when you sleep, when you shower, and how often you go to the bathroom. The nap rooms at Google were there because it was safer to stay in the office than walk to your car at 3 a.m. For my first five years, I did at least one all-nighter a week, except when I was on vacation—and the vacations were few and far between.

From here he starts trying to dig into history and religion to see how we got here. He details the history of how “work” as we define it today, was held in contempt for most of history. He then details how in the 1500s during the Protestant Reformation, work became transformed from something that the bible talks about as a universal duty to something that could be mapped to the individual:

“if you don't do not work, then you shall not eat. As I understand it, until quite recently, till that time, this was taken more liberally to mean, if human kind does not work, than human beings shall not eat. But the more literal interpretation wins out such that it reads, if each person does not work, then each person shall not eat.”

He frames this as the beginning of a shift that eventually morphed into something more total which he calls the “work ideal” which has had a powerful stranglehold on our imagination ever since. It is made up of three parts:

Work is good for you and makes you a better person

Work is an inherent good and an end in itself. It is a reason for living: “to be is to work”

Work is a supreme good held in esteem with love, goodness, beauty, truth, and peace

So this is all well and good, but what is his alternative? He does not suggest that we abandon work like many “post-work” thinkers. Instead he says we need to both redefine our conception of work to one that is founded on “care, responsibility, and attention on fineness” and to expand our imagination for a broader definitions of what it is to work beyond the current default of a full-time job.

The philosophical set of questions he leaves people with seems like a good way to start. If we are not really workers, then…

Who are we?

How did we get here?

What responsibilities do we have?

How can we put our lives together?

Do check out the talk and let me know what you think.

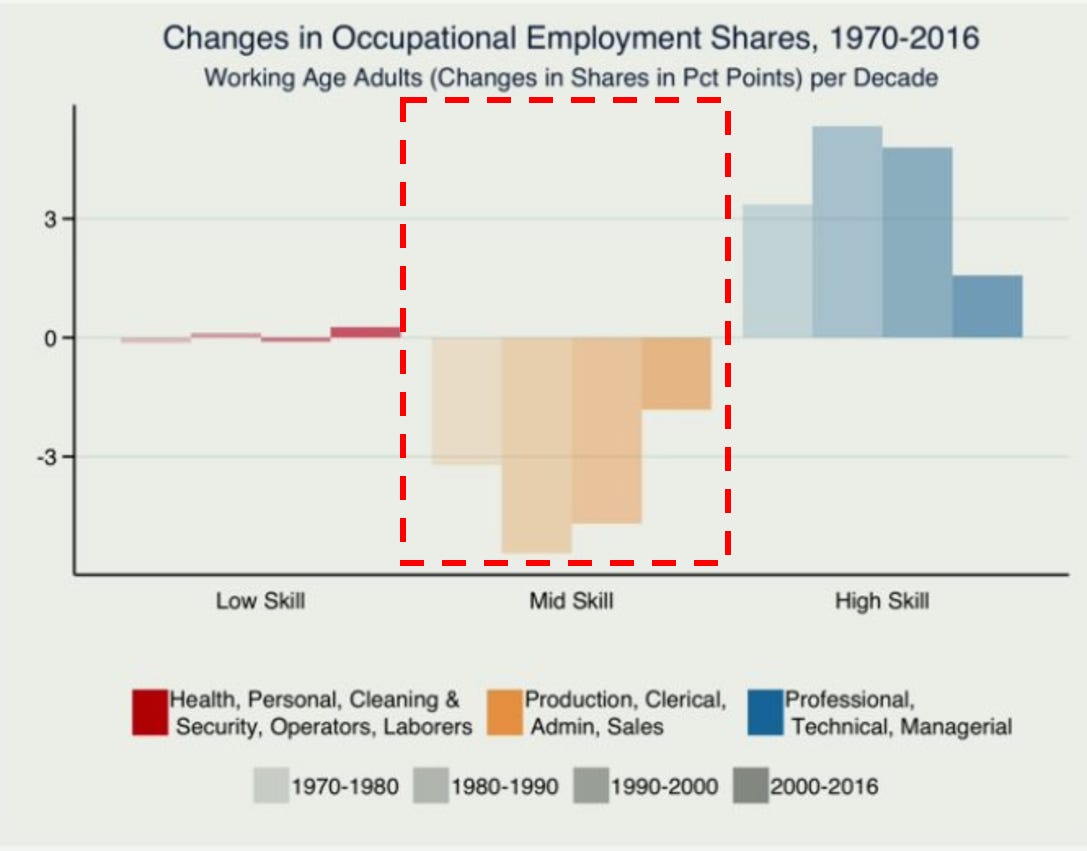

#2 David Autor on reality in our labor economy

It is easy to look at the unemployment numbers and to look around at your other knowledge-worker friends and thing the economy is humming along. Yet there is a massive transformation underway. David Autor has been putting together some incredible research on these trends:

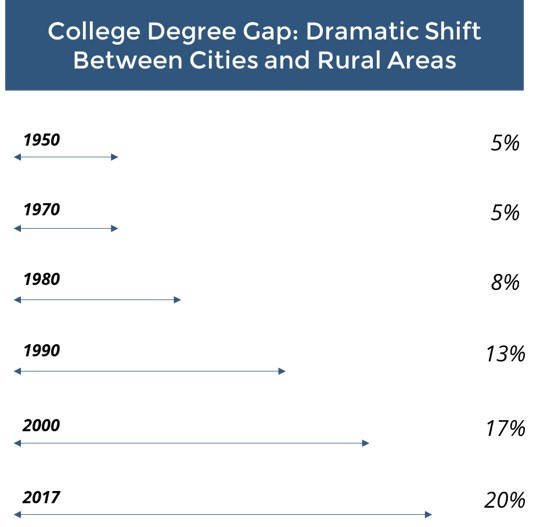

On the death of “middle-skill” jobs in cities:

There were these occupations where non-college workers did skilled work in metro areas: production work and clerical, administrative work. These were middle-skill jobs and they were much more prevalent in cities, urban areas, and metro areas than they were in suburbs and rural areas. But that began to decline in the 1970s and is now extinct. There’s nothing remaining of that.

and how cities are becoming extremely educated:

“Cities are different places than they used to be. They’re much more educated now, they’re much higher-wage, and they’re younger. They were distinctive before in the set of occupations they might have, and now they’re distinctive in extreme levels of education, high levels of wages, being relatively youthful, and being extremely diverse. You can see how this creates a growing urban, non-urban divide in voting patterns.”

…and because of these high-wage premiums, people are deciding to stay in the cities instead of leaving for the suburbs:

“the densest urban counties have become so appealing to prime-age workers that they’re now less likely to move away at life stages when previous generations have retreated to the suburbs, like when children arrive.”

I would summarize the two trends happening as:

Increasing number of high-wage, high-skill jobs in cities for people with college education

Disappearance of medium to high-wage wage “middle-skill” jobs (especially in cities) leaving people with “low-wage, low-skill” jobs in retail, outsourced support functions or other manual labor

This seems to be fueling two different types of conversations. On one side people want “meaningful work”, parental leave and the ability to work remotely. These are perhaps what Taggart might call “total workers”. On the other side are millions of people who are just trying to find some dignity in a country that values work so highly.

#3 Why Governments Are Obsessed With Employment And Maybe There Is Hope?

From Andrew Clark’s research on “happiness and economic performance” in 1997

The conclusions of the paper do not mean that economic forces have little impact on people's lives. A consistent theme through the paper's different forms of evidence has been the vulnerability of human beings to joblessness. Unemployment appears to be the primary economic source of unhappiness. If so, economic growth should not be a government's primary concern.

Yet perhaps there is some sign that the conversation may get a bit more nuanced in the upcoming elections in the US with these comments from “Mayor Pete”:

“That lost sense of identity is extremely important and it’s only going to become more urgent as automation changes the way we relate to the world, in particular it changes the way we relate to the workforce. You just can’t count on a lifelong relationship with a single employer to define where you fit into the world the way you used to…if we’re not speaking to that then I think we’re going to continue to see this kind of disaffection that has made people so ripe for the false promise being peddled by this White House that the solution is just to turn back the clock. That we can just stop these changes that are so disruptive for you. ‘We’re gonna make America Great again?’ You know what does that mean? It means ‘we’re going to stop the changes so you don’t have to change anything,’ and it’s not honest. You can't have an honest politics that revolves around the word ‘again.’”

This tension - the fact that most people still design their lives around work and the fact that it is harder than ever for so many people to realized - seems central to a lot of the debates happening in many nations across the world.

#4 Tanya Zhang & Wesley Yang: Co-Founders On Escaping The Corporate World

🎧 Listen: Web | Itunes | Overcast | Spotify | Google

Wesley Kang and Tanya Zhang are the co-founders of Nimble Made, an e-commerce clothing brand that makes “actually slim” dress shirts.

Before taking the leap to work full-time on their business, they worked in the corporate world in New York City. As first generation Asian-Americans, they had achieved “success” – good jobs, good salary. They were on their way. However, deep down both wanted something a little more. Some of Tanya’s challenges working as a freelance graphic designer on the side convinced them they should try to think a little deeper about building a brand and a business, instead of just helping other people.What we talked about:

Expectations on them as Asian-Americans

Taking the leap to entrepreneurship

How they handle being in a relationship as well as co-founders

How Tanya’s freelance work led them to think about starting a company

The uncertainty and challenges of entrepreneurship

Fostering a dog and reclaiming their daytime

How “average” sizing and approaches to life don’t work for anyone

📬 E-Mail Me

I want to make this newsletter an ongoing experiment and co-creation with the many members that read and follow along. What questions do you want me to write about? Anything you are working on that I can share? What quotes are inspiring you?

Shameless Self-Promotion

🔥 Take The Three-Week Self-Employment Challenge over at BoundlessU

💬 What questions are on your mind? Join the conversation in the Boundless slack community

☕ Interested in Working with Paul?

🔨 Get access to the Boundless toolkit and tools for self-employment here

🎁 Want to become a supporter of this humble newsletter? Support on Patreon because you want to join an exclusive society of internet newsletter supporters