September 12th, 2020 - Greetings from Charlotte, NC and welcome to the almost 200 new subscribers that subscribed this week. We’re two days into our road trip across the US and successfully camped on a private farm using a pretty cool app called Hipcamp. We then drove down to Charlotte yesterday via a stop at the beautiful UVA campus and then down the blue ridge parkway, which is even more beautiful.

This week I have another guest issue for you of someone I’ve been excited to get to know over the past year, Oshan Jarow.

Oshan has been exploring our experience of reality is shaped by our economic system. Earlier this year he published a great essay titled “Universal Basic Income and the Capitalist Production of Consciousness” which explores how capitalism and our current iteration, “hyper-capitalism” shapes who we are as people.

In that essay, he makes a powerful point about how people think about possibilities of the future that are not as dependent on the way we have worked for a long time:

The projection that we’d waste our time with idling activities like Netflix and the beach neglects that most working class humans today are overworked and barely getting by. Current notions of how we spend our ‘leisure’ time are products of, and responses to, our life conditions.

Last week we also recorded a podcast episode. You can download the podcast or watch on YouTube. On to Oshan…

Hey all, Oshan here. I’m honored to have this opportunity to write to you from Paul’s wonderful newsletter. Most of my work probes the relationship between economics and consciousness. A strange pair, I know. This short essay tries to clarify the connection, and point to why it’s important.

You’re probably familiar with the “what the hell is water” story. A fish swims by two other fish, asking them as he glides by: “how’s the water, boys?” Shortly after, one fish turns to the other with a furrowed fish-brow and asks, “what the hell is water?”

The question doesn’t land because it has never experienced anything other than water. Without this kind of relational tension - where we perceive black because of white, hot because of cold, left because of right - water never registers as something that exists in the fish’s perception. Without contrast, water remains part of the imperceptible background.

Maybe the fish who asked the question recently found herself swimming above a whale right at the moment it expelled a great big jet-stream of water from its blowhole, launching the fish beyond the water's surface and into the air. Upon falling back into the water, the fish had experienced something other than water, which created the relational tension required to register water as something to be perceived in the first place.

I’ll call this process foregrounding. Foregrounding yanks things from the imperceptible background of our lives into our fields of perception.

One of the threads running through my work - essays, podcasts, newsletters - is an attempt to foreground the economic system as a causal force in our subjective experience of what it feels like to be alive. We often take sentience, consciousness, subjectivity - whatever you call it - for granted. As if it simply is, and our lives are to be lived through that default configuration of consciousness.

Any number of folks can tell you this isn’t so. Neuroscientists can tell you that neuroplasticity - the brains capacity to rewire itself in accord with new experience - is a lifelong phenomenon. Psychedelic connoisseurs will tell you that one measly mushroom, or a small acid tab stamped with George Harrison’s face will (temporarily) reconfigure the way you experience anything in the first place. Meditators will tell you how their practice opens previously unknown states, or rooms, of consciousness.

But does economics have anything to add, any role in the configuration of consciousness?

Turns out, if you look hard enough, yes. There’s a scattered history of economists, cultural theorists, and philosophers who’ve argued that economic systems have as much to do with the construction and development of consciousness as any of the above.

What Does the Economy Feel Like?

Our experience of life is a social production. In the same way that you might run your fingers across a patch of soft, purple velvet and feel that distinctly plush, tufted, sumptuous fabric, the cultural theorist Raymond Williams writes that every historical epoch has its own ’structure of feeling’ that’s tightly coupled to its economic situation. It’s own tactile, affective qualities that run through each inhabitants experience of the world. Its own organs of perception. Philosopher Lauren Berlant puts it nicely: subjectivity is laced through with structural causality.

Another way to foreground this relationship between economics and consciousness is to point out how the possibilities available to us in everyday life determine the boundaries of what we might do, and therefore, what we might become (on this point, I like Peter Sloterdijk, who wrote “it is time to reveal humans as the beings who result from repetition.” Doing guides becoming). The historian Fernand Braudel’s deep history of capitalism, The Structures of Everyday Life, is tellingly subtitled: The Limits of the Possible.

Economic systems carve out the landscape of possibility that presents itself to the open canvas of everyday life. Like a young boy choosing from the outfits his mother hung in the closet for him, we can only pick from options that make it past economic constraints. Drunk on the apparent freedom to choose, we're oblivious to the choices that might’ve been available were we involved earlier in the selection process. We never realize the water limits our choices.

My contention is that foregrounding the economic system reveals a wealth of possibilities well beyond the familiar limits. These matter, especially for the everyday life of ordinary people.

Our failure to foreground the system is, in part, what allowed neoliberalism to close our socioeconomic imaginations. It led us to believe that, as Margaret Thatcher so imperiously put it: “there is no alternative!” It’s why, despite 40 years of widening inequality, meager growth captured by a financialized elite, languishing mental health, and ecological devastation, we continue to think and act, to abide by the system that brought us here.

Berlant leads a field known as affect theory, which asks: what does it feel like to live in this world? Her book, Cruel Optimism, asks why we continue accepting a system that so reliably fails us:

“Cruel optimism is…an analytic lever, it is an incitement to inhabit and to track the affective attachment to what we call ’the good life,’ which is for so many a bad life that wears out the subjects who nonetheless, and at the same time, find their conditions of possibility within it.”

Foregrounding the system is an opportunity to redesign the system that has so far dictated our conditions of possibility. As I explore in a recent essay, foregrounding invites a rush of possibility into the economic structures that mold our lives.

How to Foreground

How, exactly, do we foreground systems? The most common, if uncomfortable, method is to let it happen naturally, person by person, breakdown by breakdown. More & more, many of us are finding ourselves shot from the water, like fish atop the whale’s blowhole. Cascading ecological, financial, racial, and existential crises are exposing the insulated ways of thinking that so stubbornly persist.

But relying on reaching a critical mass of individual life crises to mobilize enough support to reconsider the system isn’t a satisfying strategy. How can we systemize the foregrounding process?

The French philosopher André Gorz suggests:

“But workers will not discover the limits of economic rationality [our water] until their lives cease to be wholly occupied and their minds preoccupied by work: until, in other words, a sufficiently large area of free time is open to them for them to discover a sphere of non-quantifiable values, those of ‘time for living’, of existential sovereignty. Conversely, the more constricting work is in its intensity and hours, the less workers are able to conceive of life as an end in itself, the source of all values; and the more as a result they are induced to regard it in economic terms; in other words to conceive of it as a means towards something quite other which would, objectively, be valuable in itself: money.”

Okay, so more free time for everyone. But how? He continues:

“…a policy of a staged reduction in working hours, accompanied by a guaranteed income, cannot fail to enliven thinking, debate, experimentation, initiative, and the self-organization of the workers on all the different levels of the economy and therefore to be more generative of society and democracy than any social-statist formula. This is the essential point: that control over the economy should be exercised by a revitalized society.”

I think Gorz is on to something, but since he was writing in the 80’s, his methods are dated (one cannot overstate the scale of changes to the economy between 1980 - 2020).

I’ve also sunk much digital ink (pixels?) into exploring how a basic income can open up spaces for more diversity in how we lead our lives, in the values that guide our actions, and in the trajectories of development the economy might follow.

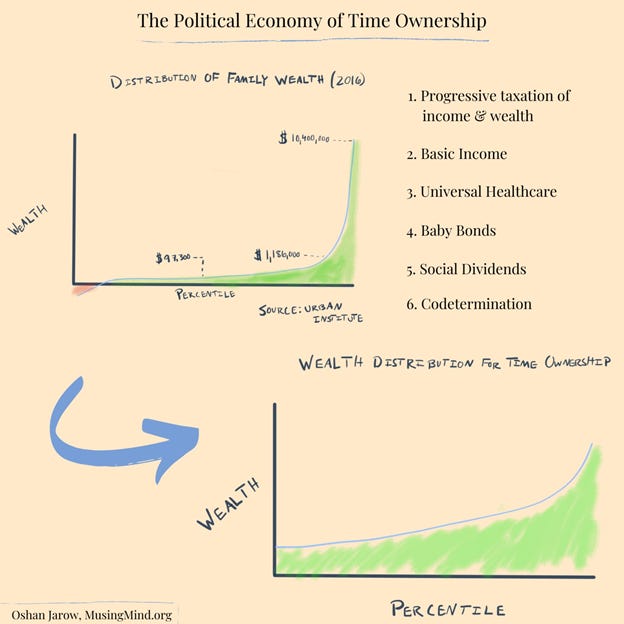

But basic income alone is insufficient to carve out the kind of free time that offers existential sovereignty. It’s insufficient to foreground the system. It’s one possible piece of a larger puzzle. In Against Time Inequality, I try to bring Gorz’s thinking into the 21st century. This means less focus on a top-down reduction of working hours, and more focus on increasing each person’s autonomy and agency - giving them the power to choose - by redesigning and democratizing the structures of capital ownership that underlie economic outcomes. Specifically, I used the idea of increasing our capacity to choose how we spend our time to tie together 6 policies: progressive income & wealth taxation, basic income, universal healthcare, baby bonds, social dividends, and codetermination.

When Braudel wrote about the limits of possibility, he framed economic progress as an expansion of the border separating the possible from the impossible. With progress, the landscape of possibility grows. But amidst this growth, we’re often hampered, stuck in previous ways of living that aren’t fully adapted to new possibilities on the margin. The economist Richard Layard calls this cultural lag:

“Market democracies, by the logic of their own success, continue to emphasize the themes that have brought them to their current position.”

In other words, the longer we swim, the deeper we sink in the water.

I think we’re perched between these two large historical forces: a rapid expansion of the limits of possibility, and a strong cultural lag. A deep submersion in antiquated waters.

But we aren’t stuck. Change is swirling all around us, perhaps all too vigorously. If we can corral some of this frenzied energy towards concrete policy changes that expand the sphere of possibility available in the everyday life of ordinary people, we just might create the kind of free time-and-space, coupled with access to resources, that existential sovereignty needs to bloom. Let’s get to work.

Thanks for reading. If you resonate with any of this, feel free to explore my writing, the Musing Mind Podcast, join my newsletter, or to reach out directly via email or Twitter.

If not, Paul’s back next week :)